The project of the Volcano Museum in Iceland shortlisted in the competition

Type – Museum

Location – Myvatn, Iceland

Date –

Iceland overwhelms you with the beauty of its nature—the breathtaking views of landscapes with lava fields, glaciers, rocky mountain ridges, stone-strewn tundra, overgrown with grasses and mosses, picturesque lakes, geysers, streams, creeks, and waterfalls. It goes without saying that Iceland is a country of volcanic land unique in its nature, which has engendered numerous myths and legends.

The Iceland Volcano Museum Complex is situated in the northern part of the Iceland, in the vicinity of Lake Myvatn and Hverfjall, one of the greatest ancient volcanoes. The north of Iceland is famous for its natural hot springs, lava rocks, lakes and, of course, Northern Lights.

Building a museum in this natural context calls for an architecture that would not only incorporate and reflect the unique natural phenomena and distinctive features of the landscape, but also become its organic extension. The construction process has to be geological in nature. Its architectural appearance must allude to some ancient structures which, over the course of time, have turned into geological formations. The museum should become, as it were, a setting for an ancient saga.

These musings, together with the subject matter of the museum, natural historical and cultural context, have led us to formulate the following founding principles for our project.

Building as Part of the Landscape

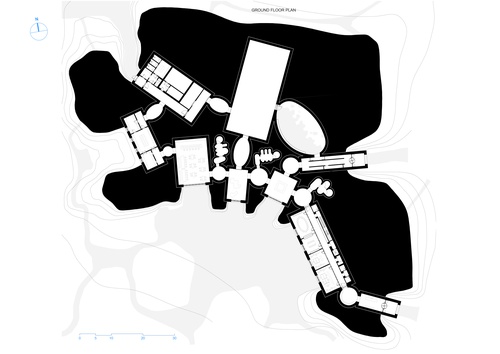

One of the longer sides of the rectangular plot is bounded by the Ring Road, which goes to Lake Myvatn in the west. The other sides face the rocky flatland, overgrown with grasses, mosses, and dwarf shrubs. On the southern side, one sees, in the distance, the grand towering Hverfjall volcano. The museum building fits organically into the landscape, but is not defined by the formal boundaries of a rectangle, though it remains inside of them. The car park for 100 cars and 10 buses also blends perfectly with the flatland. We use volcanic crushed stone for road’s paving, and the design lines are not rigid, but look as if they are naturally formed, while the many paths and trails leading to the museum act to do away with the feel of rigid, rational geometry.

We see the museum building as part of the natural park—the beginning of many interesting footpaths. From the side of the road and car park, the museum assumes the appearance of a grass-covered hill, formed as if by nature herself, with only some parts of the volumes, clad in anthracite volcanic stone, peering out. The paths and trails, flowing in all directions like streams from the car park, take you not only to the entrances of the museum complex, but also to the hill itself, and having ascended and descended it, one can carry on strolling through the flatland.

Orientation

As mentioned above, the museum complex is part of the landscape and the starting point of the walking tour in the magnificent natural park. It is likewise reflected in the orientation of the building. From the side of the road and car park it resembles a gently slanting natural hill, with slightly jutting out stone volumes of the main entrance, office entrance, staff and technical block, as well as the exhibition hall—the dominant volume.

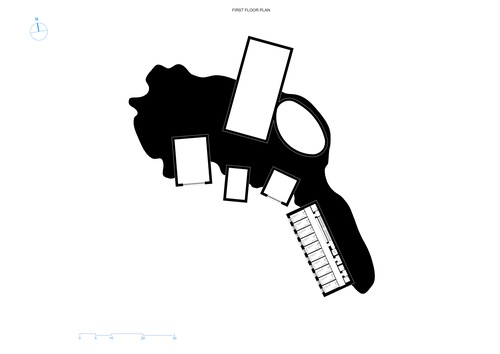

In contrast to this, on the south and southwest sides, more volumes jut out from the steep side of the hill. These are to be used mainly by visitors, office staff and other personnel. These volumes of different height, clad in lava stone, with large stained-glass windows that provide a vista of breathtaking views of the flatland, lava fields and the majestic Hverfjall volcano, coupled with the hill’s slopes, work together to form the rather small interior museum area. It appears to be concealed by the building from the human world, but open to the world of northern nature and the land of mythical volcanoes. This area is to serve as a venue for various events, perhaps concerts and performances during the midnight sun in the summer and the spectacular Northern Lights in the winter.

Cultural and Community Center

The museum is not only an exhibition space. The building also houses spaces for short-term as well as permanent employees, a cafe, and an information center. The museum is a place that can be used to host events not only for visitors and tourists, but also for local residents. Icelandic sagas, rich in events, with all the accompanying heroes, gods and creatures, born of the nature of volcanic land; the tales of spacious, high-ceilinged halls, where people gather and feast, and where stories are told and legends are made—all of this makes up the cultural, historical, and social context, which is reflected by the museum building.

The main spatial elements in the structure of the museum are the spacious, high-ceilinged halls—rectangular volumes, or “four-walled spaces,” as we call them. They reflect the primary functions of the program: the main entrance hall, information hall, exhibition hall, and cafe hall. There are other rectangular volumes: the office employee block, kitchen block next to the cafe, staff and technical block. The volumes of the main entrance and office entrance passages are likewise rectangular. These rectangular spaces face one another and are linked by passages that have circular or elliptical layout. We call these spaces that resemble lava grottos the “one-walled spaces.” In addition to this, we have created a hidden inner geyser courtyard—a space for meditation, a place under the open sky. This ellipsoidal in its layout courtyard links the volumes of the exhibition hall and main entrance passage.

Hierarchy, Proportions and Materiality

The rectangular volumes differ in size and proportion. Thus, the spaces intended for visitors of the museum, such as the information hall, exhibition hall and the cafe hall are created in accordance with the concept of the irrational proportion, based on the ratio of a square to its diagonal. However, the space of the main entrance hall, where visitors begin their tour of the rest of the museum complex, is cubic, symbolizing “the beginning.” The volume of the office block, just like the other aforementioned rectangular blocks with their designated functions, intended for office employees and kitchen staff, are created in accordance with the concept of rational proportion and represents themselves as two, three or five squares in layout.

It was important for us to employ this partly archaic concept of hierarchy and proportional structure of the spaces because this approach lends the kind of archaeological air to the architectural structure that is commonly found in ancient buildings which, as we have already mentioned, is precisely what we strove to achieve.

Thanks to this, the resulting structure gained a certain scale, appearing not as one extended building, but rather as a cluster of small houses that are partially concealed by the landscape. This, in turn, renders it reminiscent of the local architectural culture, which gave birth to the unique traditional Icelandic turf houses. It should also be mentioned that this design solution, together with the use of geothermal heating, makes the museum building energy-efficient.

Outside, the visible volumes are clad in volcanic stone, and the walls are made deliberately massive. The construction of the foundations, walls, overlaps and roofs are made from concrete that is filled with the same stone, and inside the spacious halls, except for the exhibition one, the walls are lined with oak paneling, while the grotto aisle spaces, linking the rectangular volumes, are in cast black concrete, bearing a resemblance to a volcanic cave. As you walk through these dark grottos, feeling as if you are journeying through the bowels of the Earth, you soon find yourself in the light-filled grand halls, filled with warmth, events, and the energy of life.